It’s difficult to welcome new gamers without making seasoned ones feel babied.

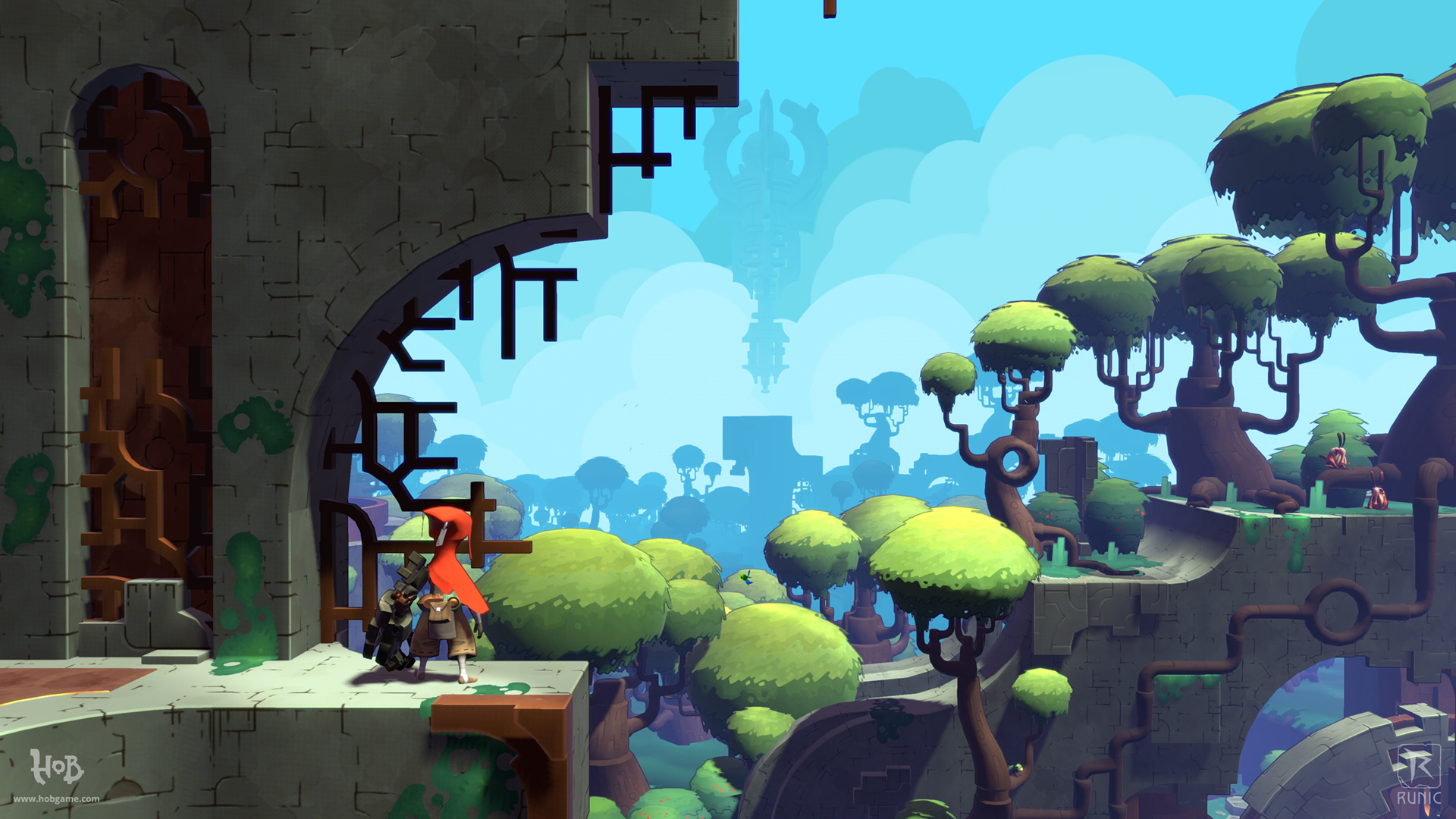

I’ve put about two hours into Hob thus far and I’ve very much enjoyed what I’ve played. The most interesting aspect so far as been its reluctance to hold my hand. Much like the classic Legend of Zelda games it draws inspiration from, you are free to explore the game’s world and mechanics at your own pace. Its deliberate lack of tutorials goes hand-in-hand with its mysterious aesthetic, making the controller just as much fun to explore as the world it takes place in.

There’s no story set up, you choose “New Game” and the main menu fades away to the game hiding behind it. A giant machine tears apart the ancient door in from of you, freeing you from your would-be prison. I know the game wants me to follow this creature, even though there’s no reason for me to trust it. That is the foundation that Hob is built on: You’re going to have to learn the game’s visual language in order to succeed.

Thankfully, Hob‘s language is concise and one I’m fluent in. I know I can move that box, even if I don’t currently posses the right tool to do so. I know these bulb-shaped plants are desirable because the game’s fixed camera allowed me to see an enemy trying to break one open. These are things I’ve learned from playing other games, so seeing them here made me feel right at home.

It begs the question, however: What if you’re not familiar with these concepts? That’s something I asked myself with another game that came out this year, Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. Just like Hob, Hellblade doesn’t feature any sort of tutorial or HUD. I was able to figure out most of what I needed to because I’ve played other 3rd person action games, but even then I didn’t know there was a block button until a few hours into the game. It made me wonder how someone unfamiliar with the genre’s tropes, or even modern games in general, would fare without any assistance.

It’s easy for long-time gamers to bemoan lengthy tutorials that, from our perspective, are teaching long established mechanics.

![]()

I’ve had it go the other too, however. I bounced right off of 2016’s Hyper Light Drifter because its concepts were a little too obtuse for my liking. Much like Hob, Hyper Light Drifter took elements from early Legend of Zelda games and fused them with more modern design aesthetics. The combat was fast and kinetic, the story was macabre and vague, but the way you had to explore the world turned me off. However, it clearly appealed to a certain group of gamers that I wasn’t currently a part of, and for that it succeeded in its own right.

It’s easy for long-time gamers to bemoan lengthy tutorials that, from our perspective, are teaching long established mechanics. I know that I need to push forward on the thumbstick to move my character, but someone who’s never played a game before may not. When we think about where a game fits into the established lexicon, we rarely take the game’s approach to on-boarding new players into consideration. Only when a game comes along that shakes the foundation of a genre do we begin to use terms like “learning-curve”, which even then suggests a fundamental understanding of a game’s roots.

For me, this lack of hand-holding is refreshing. It makes learning Hob‘s most basic rules engaging and entertaining, while allowing me to wonder about what will happen next. It also enhances its replayability because I know I won’t have to slog through 45 minutes of tutorials just to get started. Just as I know I will inevitably find a game that is too impenetrable, I also understand the need for some games to walk new players through their most basic mechanics. While I hope someday we find a solution that allows every type of player to both feel challenged and not feel left in the dark, for now I’ll have to settle for the handful of games that choose to cater to seasoned gamers at the expense of possibly turning new comers off.